Have you ever looked at a Japanese woodblock print? Here’s everything you didn’t know about Shin-hanga, an art movement originating in Japan in the early 20th century.

The artists used woodcut blocks and rolled over the blocks with paint, creating beautiful prints. Hasui Kawase was one of the most significant artists in the movement. His early career started in painting, when he studied both Japanese and Western techniques. Hasui quickly turned to woodblock printing in 1919. The major publisher of shin-hanga, Watanabe Shōzaburō, recognized Hasui genius and he became their most important artist. Many people consider Hasui’s pre-war prints the finest example of shin-haga. Unfortunately, the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 destroyed all of Hasui’s woodblocks, so the prints made before 1923 are exceedingly rare and valuable.

Hasui’s family owned a rope and thread business and he was expected to enter the family business despite his interest in art. When the business went bankrupt when Hasui was 26, it freed him to devote himself fully to his artistic passions. Hasui’s uncle, Kanagaki Robun, was an author and journalist who published the first magna. He went by the pen name Nozaki Bunzō.

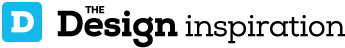

Hasui’s series of prints entitled Zojo Temple in Snow were designated by the government as an Intangible Cultural Treasure, the most prestigious honor awarded to artists in post-World War II Japan. Zojoji in Snow was his first print in the series. Made in 1922, it was reprinted more than 3,000 times.

Another print, Snow at Zojoji Temple, Shiba, is another wonderful example of shin-hanga, as it incorporated Western elements like light and mood, but with Japanese themes of famous places, landscapes, and beautiful women. Hasui traveled extensively throughout Japan. He would make sketches of the landscapes he observed and when he returned to his workshop, he would make them into woodcut prints. Hasui broke with his predecessors by depicting not only famous landmarks, but also creating scenes of the everyday people and things he saw during his travels.

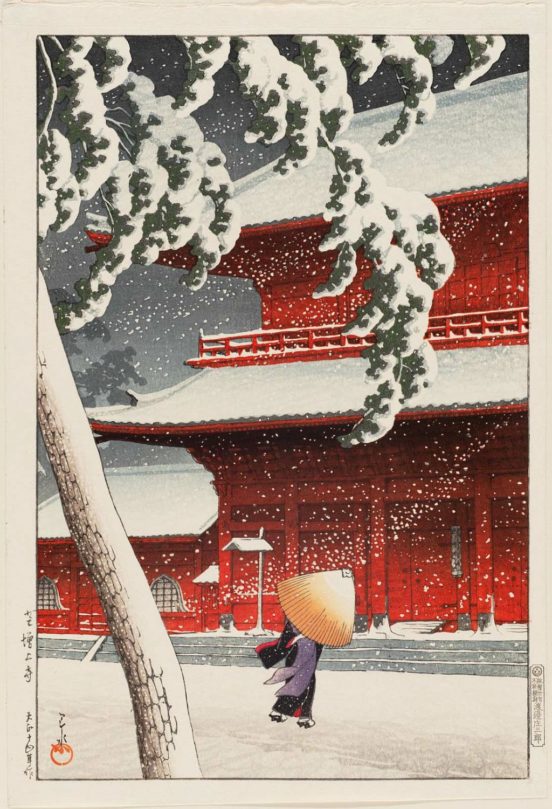

His depictions of the Japanese red temples in snow scenes are Hasui’s most well-known images, but his nighttime snow scenes are perhaps his greatest woodcuts. Hasui frequently set the scene at night by using a full moon. Moon Over Magnome is characteristic of his moonlit work. As in all of his landscapes and woodblock prints, Moon Over Magnome shows a modern take on Japan that still contains a yearning for a Japan of the past.

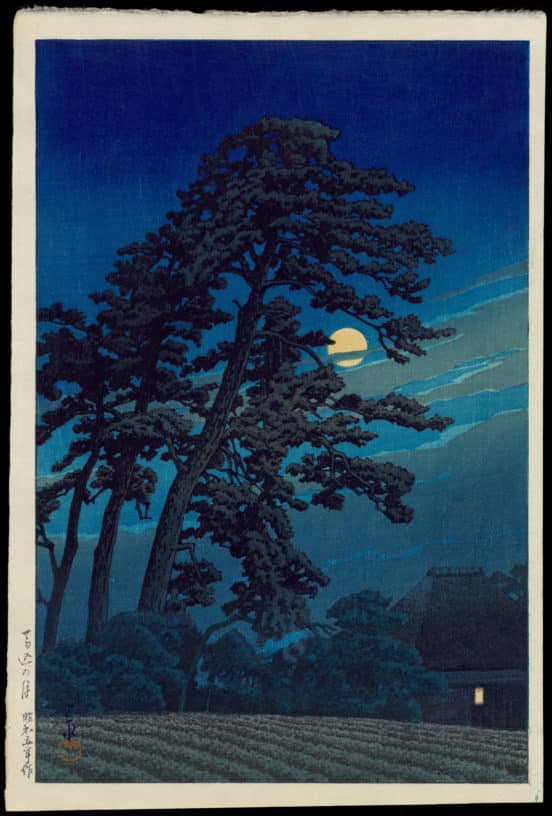

The Japanese woodblock printmaking tradition is ancient in Japan, and works from the Edo period of 1603 to 1868 used the ukiyo-e style. Hasui helped to revive this style for the 20th century, while infusing the dreamy ukiyo-e style with the modern world by incorporating concepts like realism. His Fujiya Hotel woodblock print, seen here, captures a more urban scene, which is contemporary, while still infusing the print with a Japanese spirit. Hasui is still regarded as the finest example of poise and restraint in the shin-hanga style.

Hasui continued to work until his death in 1957. Today Hasui’s prints can be seen at the Tokyo Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which has a collection of several hundred Hasui prints.